I love this book as much as the next lonely, nerdy teenager. I read it repeatedly during my adolescence, and was obsessed to the point of writing Elvish poetry in magic marker on my school briefcase, etc. Needless to say I was attracted to the baddies like Saruman, Shelob and the Nazgul, and bored to tears by the Aragorn stuff – and above all I was (and remain) completely in love with Gollum. I used to draw him all the time, and practise speaking like him, and I don’t think I’ve ever got over his death. After my teenage obsession I put Tolkien aside until my early 40s, when I re-read the whole lot in one go in preparation for the movie release. I thought I’d be really disillusioned, but I wasn’t – and I even loved the Aragorn stuff. In fact the only bit of LotR I can’t stomach is the toe-curling Tom Bombadil section. I was really nervous about the films, but I think they’re the best screen adaptation of any novel, ever.

I love this book as much as the next lonely, nerdy teenager. I read it repeatedly during my adolescence, and was obsessed to the point of writing Elvish poetry in magic marker on my school briefcase, etc. Needless to say I was attracted to the baddies like Saruman, Shelob and the Nazgul, and bored to tears by the Aragorn stuff – and above all I was (and remain) completely in love with Gollum. I used to draw him all the time, and practise speaking like him, and I don’t think I’ve ever got over his death. After my teenage obsession I put Tolkien aside until my early 40s, when I re-read the whole lot in one go in preparation for the movie release. I thought I’d be really disillusioned, but I wasn’t – and I even loved the Aragorn stuff. In fact the only bit of LotR I can’t stomach is the toe-curling Tom Bombadil section. I was really nervous about the films, but I think they’re the best screen adaptation of any novel, ever.

Monthly Archives: August 2012

27. The Lord of the Rings, JRR Tolkien (1954/55)

Filed under My top 100 novels

28. Augustus Carp, by ‘Himself’ (Henry Howarth Bashford) (1924)

An obscure gem if ever there was one. I first came across Augustus Carp in the late 70s when Kenneth Williams read it on the radio – wonder if there’s a recording of that anywhere? Finally I tracked it down in a second-hand bookshop, and I’ve probably read it once a year since then. It’s in one of my favourite sub-genres, the satirical bogus autobiography (see also Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Little Me and my own stab at it, I Must Confess). Augustus is by his own account ‘a really good man’ whose chief interests in life are eating himself to obesity, campaigning against immorality and blackmailing his employers. It’s largely set in south London, which is always a bonus. Many of the lines in Augustus Carp are in daily use in our house (‘In the full flower of his Metropolitan Xtian manhood’) and I laugh like a drain every time I open the book. First published anonymously, the book turned out to be the work of the King’s physician Henry Howarth Bashford, which is curiously gratifying given the novel’s preoccupation with unpleasant bodily ills.

An obscure gem if ever there was one. I first came across Augustus Carp in the late 70s when Kenneth Williams read it on the radio – wonder if there’s a recording of that anywhere? Finally I tracked it down in a second-hand bookshop, and I’ve probably read it once a year since then. It’s in one of my favourite sub-genres, the satirical bogus autobiography (see also Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Little Me and my own stab at it, I Must Confess). Augustus is by his own account ‘a really good man’ whose chief interests in life are eating himself to obesity, campaigning against immorality and blackmailing his employers. It’s largely set in south London, which is always a bonus. Many of the lines in Augustus Carp are in daily use in our house (‘In the full flower of his Metropolitan Xtian manhood’) and I laugh like a drain every time I open the book. First published anonymously, the book turned out to be the work of the King’s physician Henry Howarth Bashford, which is curiously gratifying given the novel’s preoccupation with unpleasant bodily ills.

Filed under My top 100 novels

29. The Diary of a Nobody, George and Weedon Grossmith (1888-89)

Comic novels feature prominently in my top 30, on the basis that there’s enough pain and misery in life without having to read about it all the time. Whenever someone offers me the latest heart-rending, soul-shattering tale of loss and grief I usually say ‘thank you very much’ and reach for something like The Diary of a Nobody. It’s one of those books that just gets funnier the more you read it, and things that seemed pointless or banal at first glance become hysterical. Originally published in serial form in Punch, the diary recounts the very boring life of Mr Charles Pooter, who commutes from his home in Upper Holloway to his desk job in the City, works, comes home and has dinner. That’s basically it. But the quality of his life – his petty annoyances, his social ambitions, his relationship with wife Carrie and son Lupin – is what this is all about. Everyday trivia like Pooter’s disastrous attempts at DIY, his dealings with tradesmen etc, are recounted in minute, compelling detail. It’s probably not everyone’s cup of tea, but once you click with The Diary of a Nobody there is no going back.

Comic novels feature prominently in my top 30, on the basis that there’s enough pain and misery in life without having to read about it all the time. Whenever someone offers me the latest heart-rending, soul-shattering tale of loss and grief I usually say ‘thank you very much’ and reach for something like The Diary of a Nobody. It’s one of those books that just gets funnier the more you read it, and things that seemed pointless or banal at first glance become hysterical. Originally published in serial form in Punch, the diary recounts the very boring life of Mr Charles Pooter, who commutes from his home in Upper Holloway to his desk job in the City, works, comes home and has dinner. That’s basically it. But the quality of his life – his petty annoyances, his social ambitions, his relationship with wife Carrie and son Lupin – is what this is all about. Everyday trivia like Pooter’s disastrous attempts at DIY, his dealings with tradesmen etc, are recounted in minute, compelling detail. It’s probably not everyone’s cup of tea, but once you click with The Diary of a Nobody there is no going back.

Filed under My top 100 novels

30. The Body in the Library, Agatha Christie (1942)

To be honest I could have put almost any Christie novel in this list, because for me the pleasure in reading them is pretty consistent. I love her for all the reasons that other people dislike her: the artificiality of her characters, the mechanical nature of the plots and the circumscribed world in which they take place. To me, detective fiction is all about creating a beautiful machine: you switch it on on page one, and it keeps working till the end. I don’t want extraneous nonsense like character development and moral ambiguity; I can get that elsewhere. So while I like Ngaio Marsh, Dorothy Sayers et al, Christie will always be the queen. I chose The Body in the Library because a) it was the first Christie I read and loved, b) it features Miss Marple who is one of my favourite fictional characters of all time and c) well, how could I resist a murder mystery set in a library?

To be honest I could have put almost any Christie novel in this list, because for me the pleasure in reading them is pretty consistent. I love her for all the reasons that other people dislike her: the artificiality of her characters, the mechanical nature of the plots and the circumscribed world in which they take place. To me, detective fiction is all about creating a beautiful machine: you switch it on on page one, and it keeps working till the end. I don’t want extraneous nonsense like character development and moral ambiguity; I can get that elsewhere. So while I like Ngaio Marsh, Dorothy Sayers et al, Christie will always be the queen. I chose The Body in the Library because a) it was the first Christie I read and loved, b) it features Miss Marple who is one of my favourite fictional characters of all time and c) well, how could I resist a murder mystery set in a library?

Filed under My top 100 novels

31. Nana, Emile Zola (1880)

There are loads of Zola novels jostling for a place on this list, particularly L’Assommoir and Au Bonheur des Dames, but Nana will always be close to my heart. It’s the first Zola I ever read, in my teens, in translation, and it’s the first one I read in French years later. It’s a great example of Zola at his ferocious best, and I’m always going to be a sucker for any book about prostitutes and backstage life. It’s also got one of the strongest story arcs of all time, taking Nana from the gutter to theatrical and ‘professional’ stardom and then all the way down to her ghastly death. Can I just say as an aside – and I don’t know if anyone will read this far – that the French novelists seem to me to be the only Europeans to rival the British. I’ve long wondered if I’m missing out on a fantastic body of novels from, say, Germany, but I’ve yet to find them.

There are loads of Zola novels jostling for a place on this list, particularly L’Assommoir and Au Bonheur des Dames, but Nana will always be close to my heart. It’s the first Zola I ever read, in my teens, in translation, and it’s the first one I read in French years later. It’s a great example of Zola at his ferocious best, and I’m always going to be a sucker for any book about prostitutes and backstage life. It’s also got one of the strongest story arcs of all time, taking Nana from the gutter to theatrical and ‘professional’ stardom and then all the way down to her ghastly death. Can I just say as an aside – and I don’t know if anyone will read this far – that the French novelists seem to me to be the only Europeans to rival the British. I’ve long wondered if I’m missing out on a fantastic body of novels from, say, Germany, but I’ve yet to find them.

Filed under My top 100 novels

32. My Antonia, Willa Cather (1918)

A few years ago I was on holiday in New England, browsing second-hand bookshops and asking my friend and host for examples of classic American literature. My Antonia was mentioned – a book that’s taught in schools in the US, but is hardly known at all in the UK. I duly bought it and read it and was blown away. The heart of My Antonia is the enduring love of Jim Burden for the spirited young Antonia Shimerda, set against the backdrop of Cather’s beloved turn-of-the-century Nebraska. Not much happens, and it’s hard to pin down the appeal of the book, but everyone else I’ve recommended it to has loved it as much as I do. Cather’s ability to relate story and emotion to the physical world, particularly the Nebraska landscape, is unmatched, and she conveys the power of love and loss without ever resorting to cliche or blustering. I nearly went for Death Comes for the Archbishop, which is just as good, but this one hit me harder.

A few years ago I was on holiday in New England, browsing second-hand bookshops and asking my friend and host for examples of classic American literature. My Antonia was mentioned – a book that’s taught in schools in the US, but is hardly known at all in the UK. I duly bought it and read it and was blown away. The heart of My Antonia is the enduring love of Jim Burden for the spirited young Antonia Shimerda, set against the backdrop of Cather’s beloved turn-of-the-century Nebraska. Not much happens, and it’s hard to pin down the appeal of the book, but everyone else I’ve recommended it to has loved it as much as I do. Cather’s ability to relate story and emotion to the physical world, particularly the Nebraska landscape, is unmatched, and she conveys the power of love and loss without ever resorting to cliche or blustering. I nearly went for Death Comes for the Archbishop, which is just as good, but this one hit me harder.

Filed under My top 100 novels

33. The War of the Worlds, HG Wells (1898)

Without doubt this book has the greatest opening paragraph in the English language, culminating in ‘intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us’. I always thought I’d love Wells’s social realist novels like Kipps more than the speculative stuff, but au contraire, I find the former laboured and mawkish while The War of the Worlds is terse, tense and profound. Of course it’s a ‘ripping yarn’ but it’s also got a lot to say about human nature and social organisation – and it’s got aliens rampaging over south-east England which, for a Surrey boy like me, is gratifying.

Without doubt this book has the greatest opening paragraph in the English language, culminating in ‘intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us’. I always thought I’d love Wells’s social realist novels like Kipps more than the speculative stuff, but au contraire, I find the former laboured and mawkish while The War of the Worlds is terse, tense and profound. Of course it’s a ‘ripping yarn’ but it’s also got a lot to say about human nature and social organisation – and it’s got aliens rampaging over south-east England which, for a Surrey boy like me, is gratifying.

Filed under My top 100 novels

34. Valley of the Dolls, Jacqueline Susann (1966)

I distinctly remember my mother devouring this book in the late 60s, and obviously I snuck a look between the covers for the ‘good bits’, particularly anything featuring the super-butch Lyon Burke. Now it’s regarded as a camp classic, largely because of the ridiculous film adaptation and Susann’s larger-than-life persona, and while I’m glad it’s still widely read I think that reputation does Valley of the Dolls a disservice. It’s actually quite a thoughtful account of women’s lives in the pre-feminist era: the book starts in 1945 and ends 20 years later, and it deals with hitherto taboo subjects like orgasms, drug addiction and breast cancer. The narrative structure – three contrasting heroines competing for the spotlight – looks simple enough, but it’s really hard to pull off. I love all three of them, and sometimes I wake up and ask myself ‘Is it an Anne day, a Jennifer day or a Neely day?’. I used to like claiming that VoD was ‘the most important post-War American novel’ and while I can’t really be bothered to have those arguments any more, I do think it should be taken more seriously than it is.

I distinctly remember my mother devouring this book in the late 60s, and obviously I snuck a look between the covers for the ‘good bits’, particularly anything featuring the super-butch Lyon Burke. Now it’s regarded as a camp classic, largely because of the ridiculous film adaptation and Susann’s larger-than-life persona, and while I’m glad it’s still widely read I think that reputation does Valley of the Dolls a disservice. It’s actually quite a thoughtful account of women’s lives in the pre-feminist era: the book starts in 1945 and ends 20 years later, and it deals with hitherto taboo subjects like orgasms, drug addiction and breast cancer. The narrative structure – three contrasting heroines competing for the spotlight – looks simple enough, but it’s really hard to pull off. I love all three of them, and sometimes I wake up and ask myself ‘Is it an Anne day, a Jennifer day or a Neely day?’. I used to like claiming that VoD was ‘the most important post-War American novel’ and while I can’t really be bothered to have those arguments any more, I do think it should be taken more seriously than it is.

Filed under My top 100 novels

35. Kidnapped, Robert Louis Stevenson (1886)

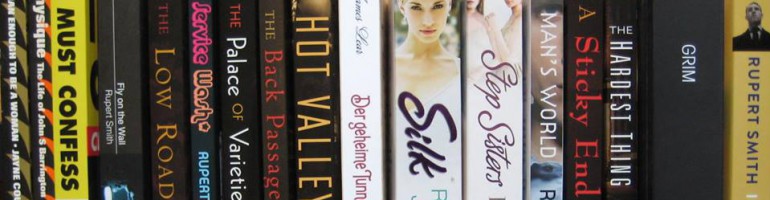

There are two principal reasons why I loved Kidnapped. First and foremost, it’s one of the most exciting adventure novels I can think of, a model of brilliant plotting, compelling narrative and sharp, magnetic characterisation. The story of David Balfour, the young ingenu sold into slavery and cheated of his inheritance by wicked Uncle Ebenezer, is probably the best coming-of-age narrative I can think of – it never labours its points, but it shows David learning from each experience and acquaintance until he’s man enough to claim what’s rightfully his. But there’s another level to Kidnapped, one which only struck me when I re-read it in my 40s – it’s a profoundly homosexual novel. I can see readers rolling their eyes at this point, but bear with me. Whether Stevenson realised it or not, the kidnapping of the young man and his experiences at the hands of older, more powerful men is fraught with erotic energy, and his friendship with the charismatic Alan Breck is highly romantic. Some critics point to The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde as ‘proof’ of Stevenson’s homosexual leanings, and I can see their point – but for me, Kidnapped is the dead giveaway (and the better novel). In fact, this was the book that inspired me to write the first of my James Lear novels, The Low Road, which is a sexed-up version of the same basic story.

There are two principal reasons why I loved Kidnapped. First and foremost, it’s one of the most exciting adventure novels I can think of, a model of brilliant plotting, compelling narrative and sharp, magnetic characterisation. The story of David Balfour, the young ingenu sold into slavery and cheated of his inheritance by wicked Uncle Ebenezer, is probably the best coming-of-age narrative I can think of – it never labours its points, but it shows David learning from each experience and acquaintance until he’s man enough to claim what’s rightfully his. But there’s another level to Kidnapped, one which only struck me when I re-read it in my 40s – it’s a profoundly homosexual novel. I can see readers rolling their eyes at this point, but bear with me. Whether Stevenson realised it or not, the kidnapping of the young man and his experiences at the hands of older, more powerful men is fraught with erotic energy, and his friendship with the charismatic Alan Breck is highly romantic. Some critics point to The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde as ‘proof’ of Stevenson’s homosexual leanings, and I can see their point – but for me, Kidnapped is the dead giveaway (and the better novel). In fact, this was the book that inspired me to write the first of my James Lear novels, The Low Road, which is a sexed-up version of the same basic story.

Filed under My top 100 novels

36. New Grub Street, George Gissing (1891)

This is a book that should be pressed into the hands of all aspiring writers before it’s too late. New Grub Street is the tale of two young men, the sensitive literary novelist Edwin Reardon and the pushy, cynical journalist Jasper Milvain. Their friendship and rivalry allows Gissing to dissect the eternal arguments about art vs commerce – and apart from technology, little has changed in the 120 years since it was published. There’s much else to admire in New Grub Street. It’s one of the best London novels of the late 19th/early 20th century, with a real feeling for the grit and grime that make up everyday life in the city (and if I remember correctly it’s one of the earliest novels I’ve read in which characters take the Underground, which made a big impression). The narrative is lively and sharp – Gissing is one of those writers who form a bridge between the high Victorianism of Dickens et al, and the terser post-War style of Waugh, Maugham etc. I’ve loved everything I’ve read by him, and particularly recommend Born in Exile, The Odd Women and In the Year of Jubilee – but this is the masterpiece, not least because it seems to have grown in relevance.

This is a book that should be pressed into the hands of all aspiring writers before it’s too late. New Grub Street is the tale of two young men, the sensitive literary novelist Edwin Reardon and the pushy, cynical journalist Jasper Milvain. Their friendship and rivalry allows Gissing to dissect the eternal arguments about art vs commerce – and apart from technology, little has changed in the 120 years since it was published. There’s much else to admire in New Grub Street. It’s one of the best London novels of the late 19th/early 20th century, with a real feeling for the grit and grime that make up everyday life in the city (and if I remember correctly it’s one of the earliest novels I’ve read in which characters take the Underground, which made a big impression). The narrative is lively and sharp – Gissing is one of those writers who form a bridge between the high Victorianism of Dickens et al, and the terser post-War style of Waugh, Maugham etc. I’ve loved everything I’ve read by him, and particularly recommend Born in Exile, The Odd Women and In the Year of Jubilee – but this is the masterpiece, not least because it seems to have grown in relevance.

Filed under My top 100 novels